Català (Catalan)

Català (Catalan)  Español (Spanish)

Español (Spanish)

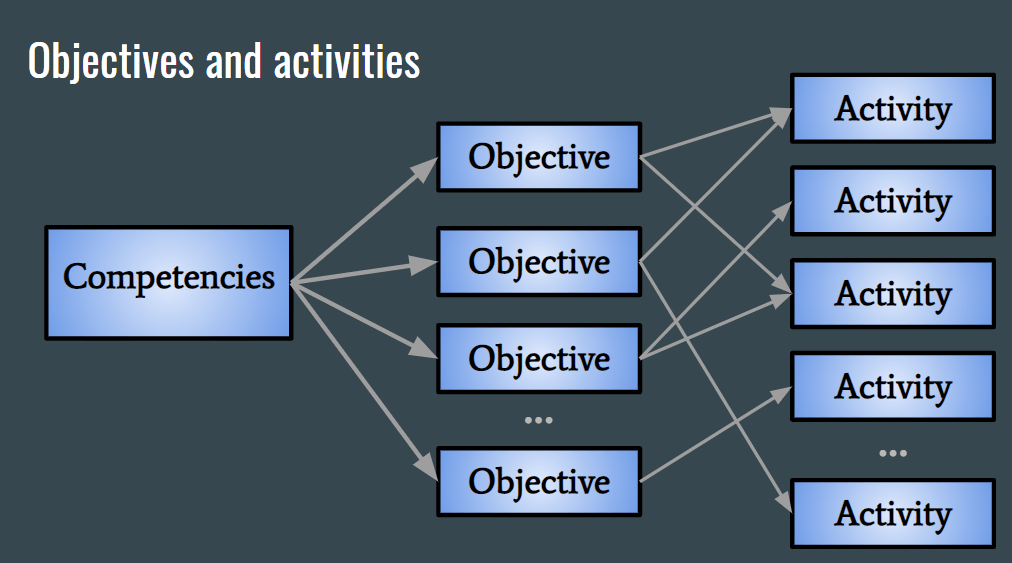

There is something that doesn’t fit at all and that is very common among teachers: the way in which final grades are calculated (quarter, project or course grades). Let’s suppose that we programme competently. Based on some competencies, we set some objectives (course, term, unit or project). To achieve these objectives, we design activities that the students will have to carry out. Some are more guided, others more open (within the objectives to be achieved). In the classroom, we carry out actions so that the students know the objectives and make them their own. While developing the activities, we make formative assessments: we give clear criteria to evaluate (self-evaluation, co-evaluation and heteroevaluation), we give feedback… From this feedback the students improve the tasks. In addition, they periodically review the objectives initially set to see if they are getting closer and make decisions about them.

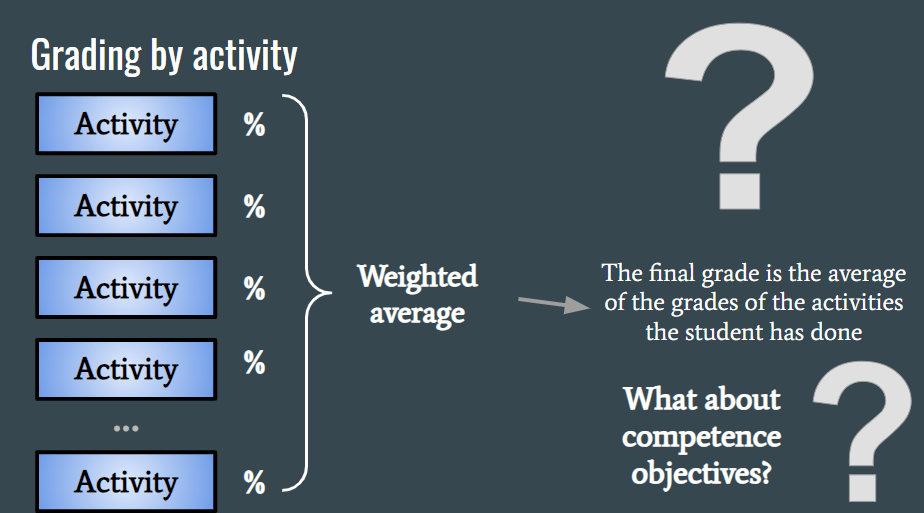

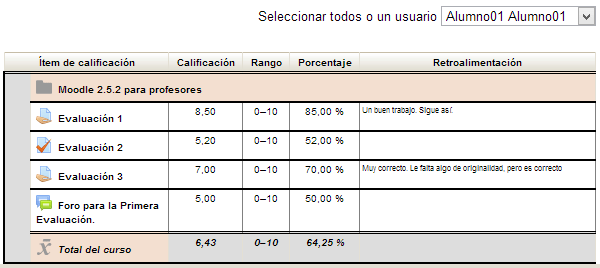

And when it comes to grade? Most teachers make a weighted average of the activities. For each activity or category of activities they assign a percentage and calculate the final grade.

As you can see in the picture, we do not look at the degree of achievement of the objectives. We end up looking at the average quality of the activities the students have given us. Surely the grade (number) will not be different from the grade by objectives that I propose, but we lose a good opportunity to continue doing formative evaluation. If we have planned with competence objectives, I think that we should also make the qualification based on the objectives.

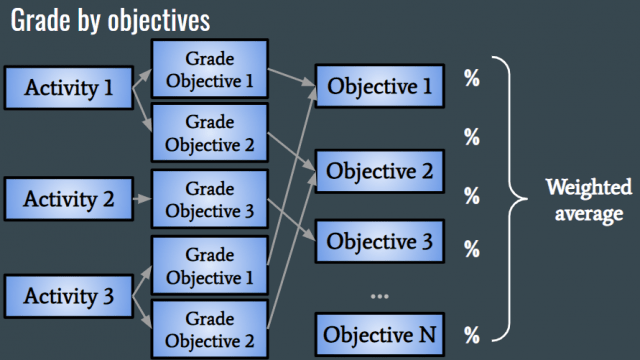

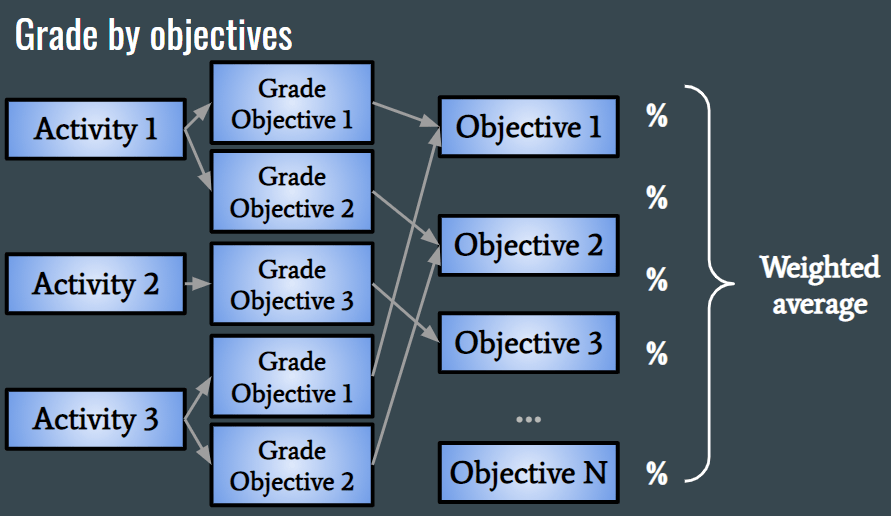

And what does it mean to grade by objectives? Simply that we don’t grade tasks in a global way, but rather, for each task we decide to grade (which doesn’t have to be all that we do with the students), we look at the level of achievement of the objectives.

Apparently it may seem that Figure 2 and Figure 3 are not very different. In the end, they both make a weighted average. But Figure 3 clearly focuses on the objectives. We are able to establish a level of achievement of the objectives in a reasoned and argued way. And, if we communicate this to the student, we reinforce formative assessment. When I speak of communicating, logically, I do not speak only of the achievement (whether with a numerical score or achievement) but also with the corresponding comment.

So the student receives the objectives we wanted to achieve, the degree of achievement and a commentary that explains what this degree of achievement is based on and guides them to improve it.

On the other hand, following the classical model in Figure 2, the student can only receive one grade per activity, but he does not have to say anything, since the activities are complex. It is true that the comment will help to focus, but the student will not have the vision of the achievement of a specific objective, since an objective is worked on in more than one activity.

For me the advantages are clear:

- Teachers must design the activities very well so that they really serve to achieve the objectives.

- Teachers can evaluate many aspects in each activity, but they only grade those aspects that they are sure they have worked on in the classroom. How many times do we grade activities taking into account criteria that we have not worked on in class but that the students were already supposed to know about?

- The student knows at all times why they are doing an activity, what they should learn.

It may seem silly and, as I said before, it probably won’t change our overall grade, but I think it can help both students and teachers to take advantage of the grade to also make explicit what we want to achieve and whether we are achieving it or not.

Let me give a common example: an oral presentation. If we use grade by objectives, we will have to be very clear about what competence objectives this activity corresponds to. If, as would seem logical, it corresponds to some objective of the oral expression competence, we will have to give clear criteria to the students in this sense. Look for moments of rehearsal, feedback from classmates… We may also propose the activity for some objective of digital competence. We will also have to give clear criteria on how this supporting digital presentation should be made. After rehearsals, evaluations and feedback, one day we will make the grade for this oral presentation. If we do not give the student a single overall activity grade, but rather one for each objective (two in this example), the student will see where he or she needs to improve. As we do other activities, she or he will see if improve on the repeated objectives.

The raters of the usual virtual learning environments (Moodle, Classroom…) or specific applications, follow the logic of Figure 2.

It is true that you can “cheat”. You can define more activities of the account (Activity 1 according to objective 1, Activity 1 according to objective 2, etc.) and define categories that are the objectives. You will end up with totals of categories which will be the objectives I indicate in Figure 3. It is simply to rethink the calculation of qualifications, which is certainly not very important in the face of the challenge of formative evaluation, but neither should we continue to do it as usual without reflection.